Is there such a thing as “blind chance”? Enter the realm of cause and effect and lining performance. Failing to see sulfide contaminants on a so-called ready-to-be-coated steel surface may be like not seeing the bullet in the chamber in a game of Russian roulette — not necessarily good for longevity in either case.

Worldwide, many thin- and thick-film innovative polycyclamine-cured epoxy linings have performed admirably in oil patch, high-temperature service for tank, vessel and pipe spool internals. Notwithstanding, with ever-increasing temperatures and pressure and chemical resistance requirements in oil and gas environments, the demands placed upon linings are becoming more stringent.

This article investigates whether the performance of these linings could be enhanced by first abrasive blasting the steel substrate and then providing a subsequent application (and removal) of a unique chemical reagent to remove deleterious sulfide contaminants, improve lining performance in aggressive immersion service conditions and potentially extend the life-cycles of the applied linings.

Accelerated laboratory investigations were carried out on a set of reagent-treated, and untreated, carbon steel test panels. Sets of panels were lined with a three-coat, thin-film solvent-borne epoxy novolac coating or a single coat solvent-free, thick-film polycyclamine-cured epoxy.

Characterization of the lining performance, the lining-steel interface and efficacy of the sulfide removal reagent was achieved using autoclave (NACE-TM0185), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM/EDX) and X-Ray diffraction (XRD).

Proper surface preparation for the application of lining systems is fundamentally crucial to long-term coating success. Carbon steel that has been abrasive blasted to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1, “White Metal Blast Cleaning” standard has rightly undergone scrutiny as the benchmark of lining performance when it is ensured that soluble chlorides and sulfates are kept below threshold levels where they would initiate lining failure. Predictors of successful or failure-prone lining applications in the real world include the influences of surface profile, peak height and peak count density, and cleanliness of the steel substrate. Importantly, from a surface profile and morphology viewpoint, a deeper profile with a greater surface area is required for these linings1-4. Furthermore, in earlier investigations the authors contend that with single-coat and solvent-free thick-film lining applications, the peak height of the profile should preferably be 3-to-4 mils and be jagged as opposed to evidencing a peen pattern (peak height, peak density and coating rheology are all important factors)1. From a surface cleanliness viewpoint, much has been discussed in the literature about the deleterious effects on lining performance by non-visible contaminants, notably soluble salts5-8. With an industry emphasis on an understanding of the effect of anions such as chlorides, sulfates and more recently nitrates (for example flash rusting, osmosis and blistering of linings) the effect of cations and insoluble sulfides has received comparatively scant attention.

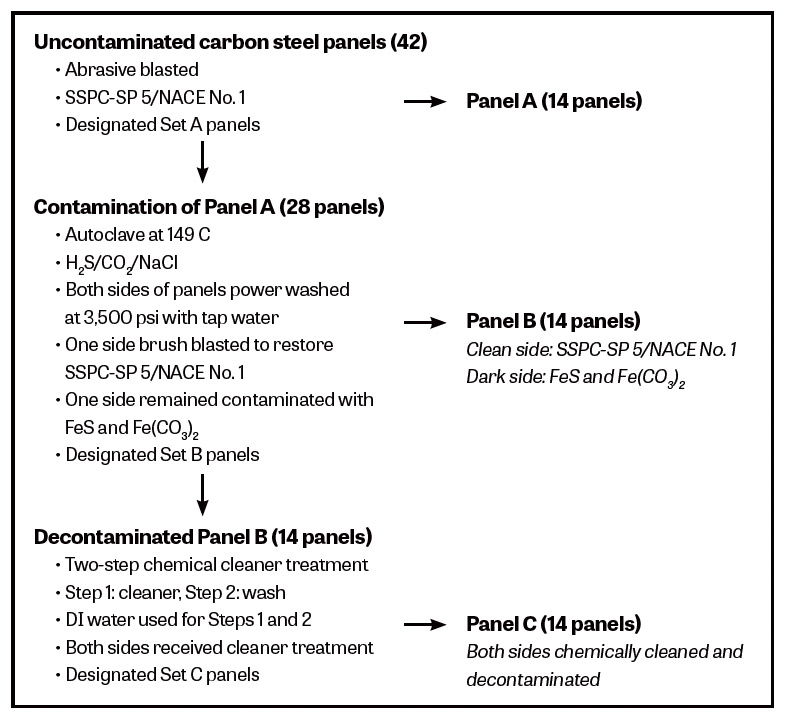

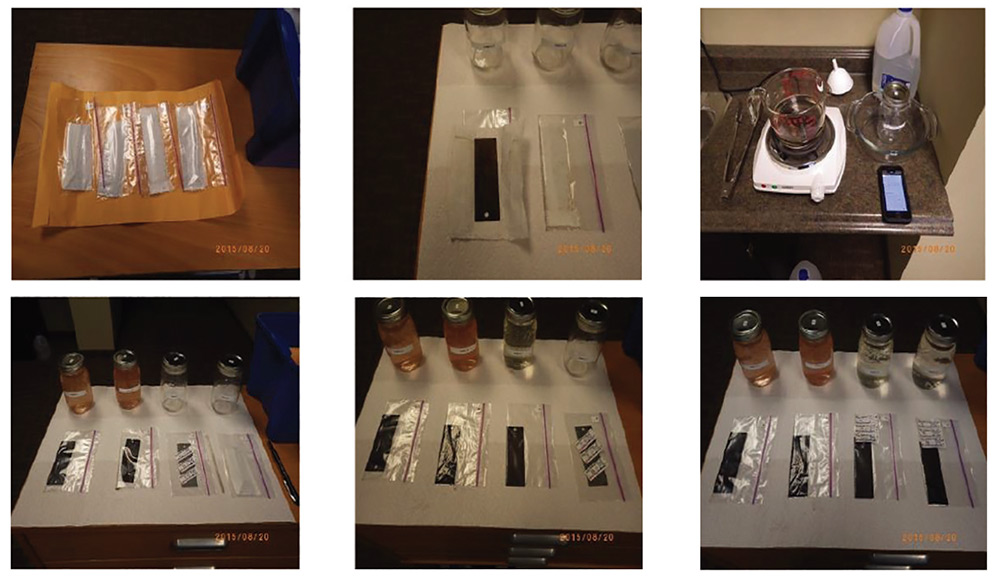

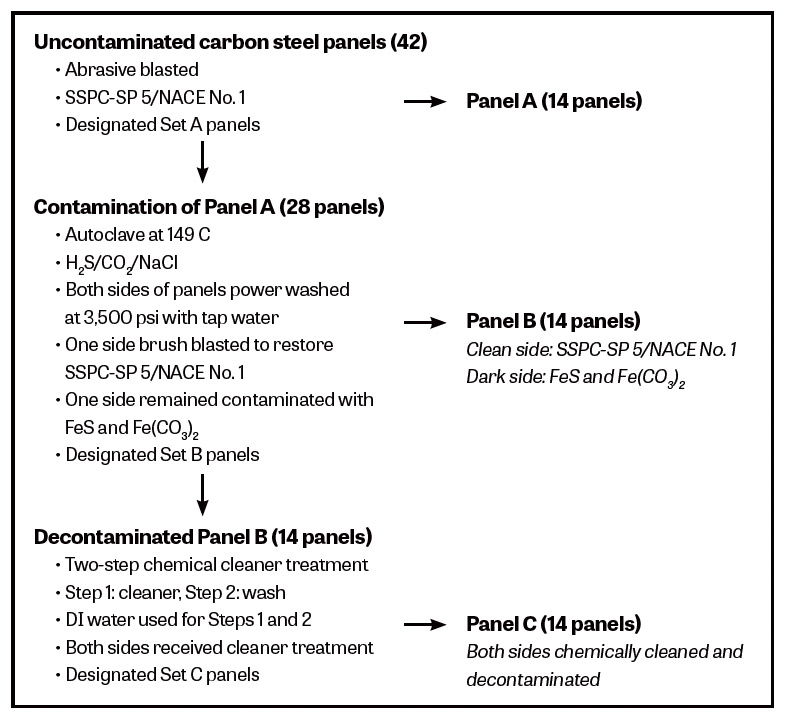

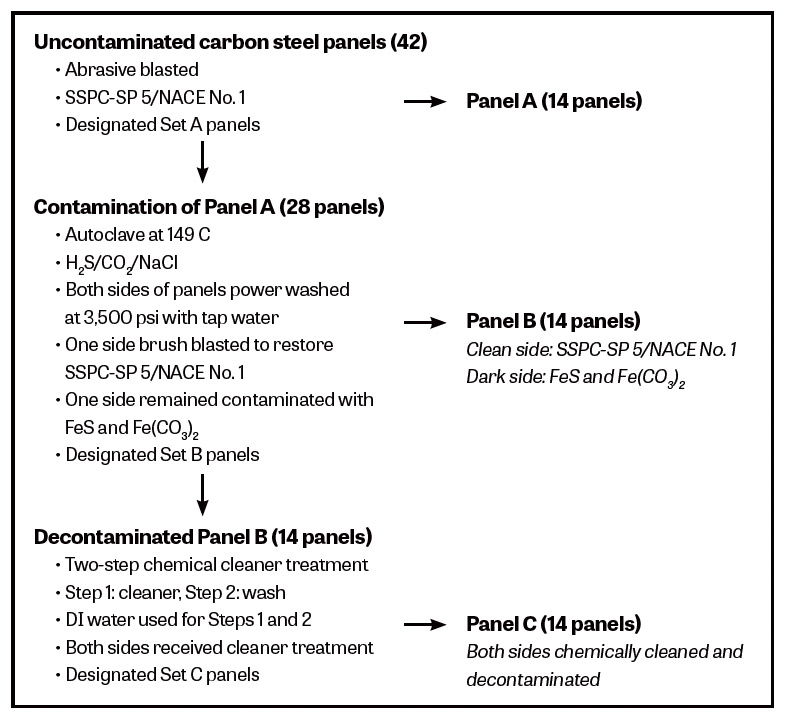

Fig. 1: Preparation and treatment of 42 panels prior to coating application.

Fig. 1: Preparation and treatment of 42 panels prior to coating application.

All figures courtesy of the authors unless otherwise noted.

Iron sulfide species are an ever-present reality in the oil and gas, mining and wastewater industries. Given that iron sulfide is cathodic to steel, and often the scourge of many industrial processes, this investigation was spurred by the authors’ curiosity to evaluate lining performance on carbon steel that had been intentionally contaminated by iron sulfide. Iron sulfide may form a thin adherent protective layer on steel surfaces, or a thick, porous detached layer depending upon the pH, H2S concentration, temperature, flow rate and pressure9. When iron-sulfide-fouled surfaces are intended to be coated, it is imperative that any residual iron sulfide or other contaminants are removed. Any iron-sulfide deposits remaining would act as both a barrier between the coating and substrate that may affect coating adhesion and become a possible corrosion initiation site due to a cathode-anode reaction when sufficient permeation of an aggressive solution through the coating occurs.

Previous autoclave and EIS studies carried out by the authors on coated panels subjected to 149 C (300 F) in acidic gases (10-percent H2S, 10-percent CO2, 80-percent CH4), 5-percent aqueous sodium chloride solution, and sweet or sour crude oil, had indicated that a proprietary post-abrasive-blast, water-based cleaner and surface decontamination process appeared to show considerable merit10. Yet studies reported elsewhere on soluble salt removal from steel and coating performance concluded that the same cleaner and decontamination process (using tap water and not deionized water) had neither a positive nor negative effect on the performance of ten atmospheric coating systems or on four internal lining systems11, 12.

The primary interest in the present investigations centered on A) the efficacy of the post-blast chemical cleaning treatment to remove insoluble iron sulfide contaminants and the difference in lining performance with or without the chemical treatment, and B) comparing and contrasting the metal surface after abrasive blasting and post-blast chemical treatment.

The cleaner and decontamination procedure was touted to remove both soluble salts and insoluble sulfides (authors’ emphasis), carbonates and oxides, and afford a residue-free and so-called passivated iron layer on the steel substrate. Furthermore, it appeared to have improved the performance of a thin-film epoxy novolac tank lining system applied to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal standard (jagged profile of 3-to-4 mils) in our previous studies10. How? The epoxy novolac lining blistered in the conditions tried on a white metal surface that had not received the chemical treatment. In contrast, the same epoxy novolac lining did not blister under the experimental conditions after having been applied to the white metal surface post treated with the surface cleaner decontamination procedure. Yet lingering questions remained.

-

Were the results repeatable and therefore, other things being equal, able to genuinely demonstrate the efficacy of the post-abrasive-blast-applied, water-based cleaner to enhance the adhesion and performance of the lining system?

-

Did the cleaner and decontamination process serve as an effective, complementary and arguably necessary treatment to abrasive blasting? Did they decontaminate the surface and remove non-visible and insoluble iron sulfide contaminants?

-

Did the cleaner “passivate steel” as reported in the literature?13

-

Was the steel surface modified by the cleaner in some unknown way?

-

As for “blind chance,” did the cleaner unload the gun?

These questions made the present investigations exhilarating from a pioneering perspective. Read on for the answers.

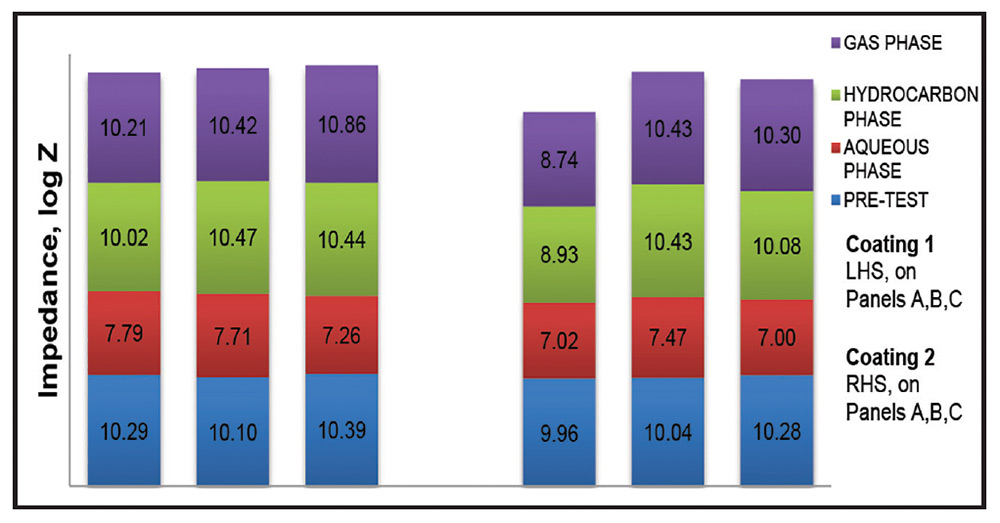

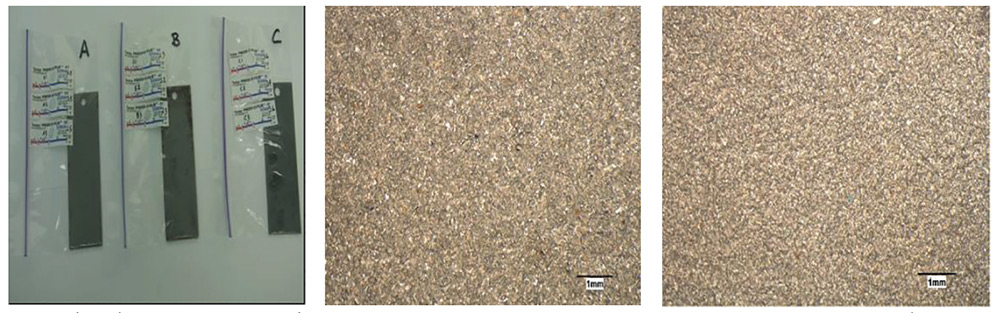

Fig. 2: Examples of deliberately contaminated panels.

Fig. 2: Examples of deliberately contaminated panels.

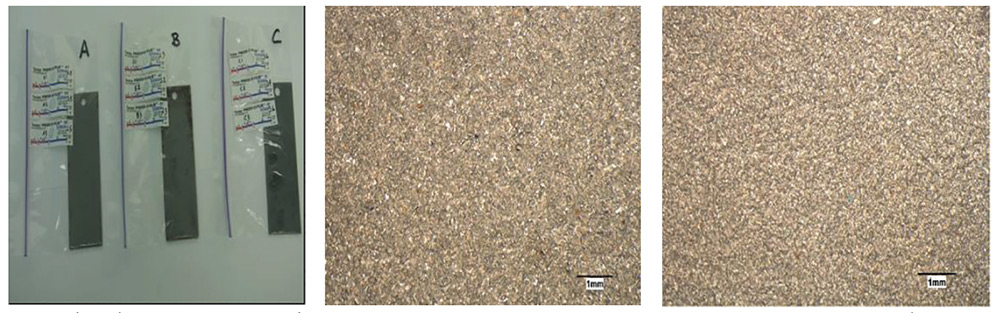

Fig. 3: Examples of pre-test panels. (Left to right): Coating 2-Panel A, Coating 1-Panel B, Coating 2-Panel B and Coating 1-Panel C.

Fig. 3: Examples of pre-test panels. (Left to right): Coating 2-Panel A, Coating 1-Panel B, Coating 2-Panel B and Coating 1-Panel C.

Fig. 4: Coating 1 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C.

Fig. 4: Coating 1 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C.

Candidate Surface Decontamination Technology Chemical Cleaning

A two-step decontamination process was intriguing in that it was stated to remove deleterious soluble salts, flash rust and insoluble metal sulfides from carbon steel substrates. This process was said to be accomplished first by application of a proprietary acidic cleaner, then followed by the application of an alkaline wash to neutralize the substrate prior to a coating application.

In Step 1, a non-toxic and eco-friendly acidic cleaning material was spray-applied as a gel to abrasive-blasted steel panels. The cleaner consisted of a powdered mixture added to deionized water. The mixture consisted of citric acid to afford the desired acidic, dispersing and free-rinsing properties, and a poly-sugar thickening agent to achieve vertical cling properties of the gel. Other additives facilitated removal of water-soluble contaminants such as chlorides and sulfates, and insoluble contaminants such as metal sulfides and flash rust. In most instances, the typical application of the cleaner would be 15 mils wet-film thickness (WFT), with a thirty-minute dwell time.

In Step 2, a power wash rinse of the cleaned substrate was undertaken using an alkaline, non-toxic, acid-neutralizing fugitive amine dissolved in deionized water. The latter ensured that an essentially chemical-free surface is achieved once the substrate is dry. The alkalinity of the wash combined with the reactive and acidic gel treatment ensures that a neutral effluent is obtained. Any portion of the rinse that does not neutralize the acidic gel, volatilizes off the metal substrate with the water. Because the chemistry used is free-rinsing, the resulting surface has a very low conductivity and is naturally in a passive state due to blocking of reactive sites that upon drying would otherwise flash-rust upon exposure to air.

Table 1: Coating 1 Autoclave Analysis

prima facie

149 C, 250 psig, 10% H2S, 10% CO2, 80% CH4, Sour Crude, 5% NaCl in Distilled Water, 96 hrs.

|

149 C, 250 psig, 10% H2S, 10% CO2, 80% CH4, Sour Crude, 5% NaCl in Distilled Water, 96 hrs. |

Coating

1 |

Avg.

DFT |

Adhesion Rating

(ASTM D6677) |

Blistering

(ASTM D714) |

Impedance (log Z @ 0.01 Hz)

(ASTM D6677) |

|

Pre-Test |

Water |

HC |

Gas |

Water |

HC |

Gas |

Pre-Test |

Water |

HC |

Gas |

|

1A |

13.0 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

N |

N |

N |

10.29 |

7.85 |

9.99 |

10.08 |

|

2A |

14.3 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

N |

N |

N |

7.74 |

10.05 |

10.33 |

|

1B |

14.0 |

8 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

N |

N |

N |

10.10 |

7.79 |

10.33 |

10.09 |

|

2B |

13.8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

F#2 |

N |

N |

7.63 |

10.60 |

10.75 |

|

1C |

16.4 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

N |

N |

N |

10.39 |

7.91 |

10.78 |

11.01 |

|

2C |

15.0 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

N |

N |

N |

6.61 |

10.10 |

10.71 |

-

DFTs were measured for each coating and each phase. Average DFT reported.

-

HC = hydrocarbon.

-

Panels A – Applied to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 abrasive blasted steel.

-

Panels B – Applied to panels above which were then deliberately contaminated with gaseous H2S (10%) and NaCl solution (5%), washed with tap water and brush blasted on one side.

-

Panels C – Applied to Panels B treated with the chemical cleaner.

Candidate Epoxy Linings

Based on earlier studies, a thin-film multi-coat solvent-borne epoxy novolac coating and a thick-film single-coat solvent-free polycyclamine-cured hybrid epoxy coating were chosen for the present investigations. Each lining is known to be well-suited to the oil and gas industry for new construction as well as maintenance and repair projects for tanks, vessels and pipe spools.

In earlier work, with a four-day autoclave test at 149 C under a 10-percent H2S, 10-percent CO2, 80-percent CH4 gas mixture, a sour crude hydrocarbon phase, and a 5-percent NaCl water phase, the solvent-borne lining had indicated a pass or fail performance-dependency in the aggressive water phase based on the presence (pass) or absence (fail) of the surface decontamination cleaner treatment10.

While the solvent-free epoxy lining system had not been investigated in terms of the efficacy of the cleaner, the fact that the solvent-free epoxy lining system ranked number one in three third-party independent laboratory tests (out of nine epoxy candidate systems in each test) warranted its inclusion as the prima facie solvent-free lining in the current test program. Of great interest was the need to determine whether the performance of this lining improved or diminished using the surface cleaner as a complementary treatment to panels that had been abrasive blasted to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal.

Coating 1

Coating 1 was applied in either a two- or three-coat application to achieve approximately 12-to-15 mils total dry-film thickness (DFT). A solvent-borne, thin-film epoxy novolac, Coating 1 possesses a three-dimensional (3-D) molecular network. Spanning decades, Coating 1 has an extensive worldwide track record in the lining of tanks and vessels in the oil and gas industry. It possesses excellent hydrolytic, thermal (up to 121 C [250 F]) and chemical resistance. Coating 1 cures at temperatures as low as 10 C (50 F).

Coating 2

Coating 2 was applied in a one-coat application at 20-to-25 mils by single-leg spray equipment. Coating 2 was a new-generation, rapid-cure, solvent-free epoxy lining with a longer pot life than most rapid-curing, single-coat solvent-free epoxy linings. As with Coating 1, Coating 2 possesses excellent hydrolytic, thermal (up to 149 C) and chemical resistance. Coating 2 cures at temperatures as low as 5 C (41 F).

Fig. 5: Coating 2 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C.

Fig. 5: Coating 2 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C.

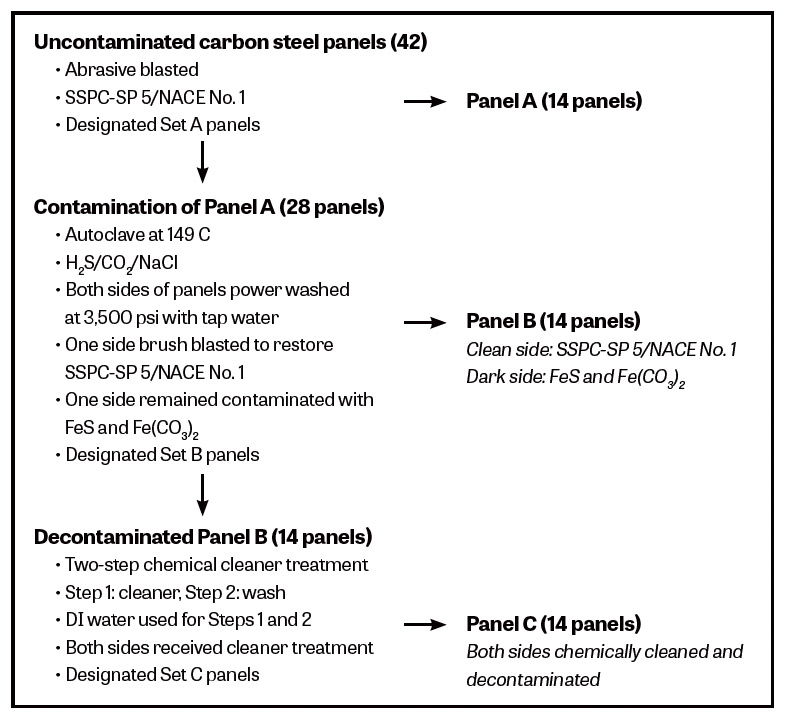

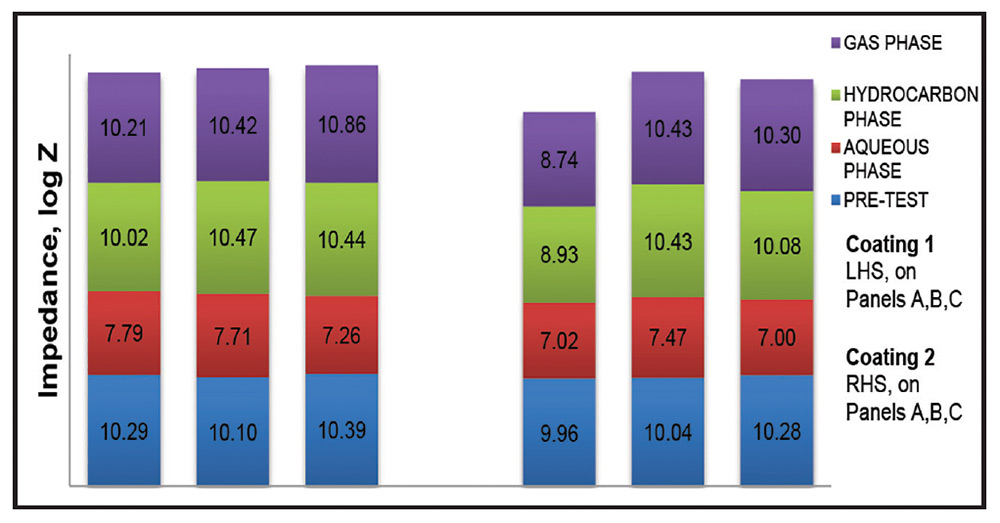

Fig. 6: Impedance, pre- and post-autoclave exposure.

Fig. 6: Impedance, pre- and post-autoclave exposure.

Experimentation

Preparation and Treatment of Steel Panels

Figure 1 is a schematic outline of the preparation of carbon steel panels designated as A, B and C.

Uncontaminated Carbon-Steel Panels

Using staurolite 20/40 abrasive media, 42 ASTM A36 carbon-steel panels at 4.5-by-1.5-by-1/8-inches were abrasive blasted to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal blast to achieve a sharp angular profile in the range of 2.5-to-4 mils. Abrasive blasting was performed by a reputable coating contractor. Fourteen of these panels were set aside and designated as Set A.

Deliberately Contaminated Carbon-Steel Panels

The remaining 28 bare panels were deliberately contaminated by exposing them to a gaseous phase of 10-percent H2S, 10-percent CO2, 80-percent CH4, and an aqueous phase of 5 percent NaCl, in an autoclave for four days at 149 C and 250 psig. Figure 2 shows the rusted panels after their removal from this exposure. This contamination procedure was undertaken to ensure that a significant amount of black iron sulfide was formed on the steel panels and that the steel was also contaminated with iron carbonate and chlorides.

After taking some conductivity measurements, the 28 deliberately contaminated panels were then pressure washed on both sides at 3,500 psi with regular Alberta tap water. One side of the panels was then abrasive swept to restore the clean and original SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 condition and the other side did not receive further abrasive sweeping and turned dark over time. Fourteen of these panels were set aside and designated as Set B.

Decontaminated Carbon-Steel Panels

Both sides of the remaining 14 panels were designated as Set C and treated with the cleaner and surface decontamination gel almost two weeks later. Nineteen liters (five gallons) of the gel was prepared by adding 2.4 kilograms (5.3 lbs.) of the powdered mixture to the appropriate amount of deionized water and mixed for about ten minutes using a squirrel cage mixer.

The test panels were treated by exposing the entire panel to the acidic gel cleaner in a ziplock bag. This technique was used in order to avoid exposing the clean front (washed and abrasive-blasted) and dark back (residual iron sulfide contaminant) panel sides individually. An aliquot of gel was poured into the bag with three or four test panels inserted. This ensured that the panels did not touch one another. Thereafter, the panels had a 30-minute exposure to the gel, with the bag being flipped-over at the 15-minute interval. The initial panels turned the gel dark grey.

The panels were then placed on a polymer-based sink protector and placed inside a plastic kitchen drying rack. All the panels were then power washed on one side with a 1-percent solution of alkaline rinsing aid in deionized water using a low-pressure, 4,000 psi pressure washer (equipped with a standard ‘V’ spray tip). Using latex gloves, the panels were then turned over and the reverse side of each panel was power washed as above.

Given that only about 90 percent of the dark side of the panel became clean, in accordance with the technical data sheet (TDS) of the chemical cleaner, the panels were retreated and rinsed a second time. The panels were left exposed under indoor ambient conditions. Prior to the first attempt to ship the panels, it was noticed that a sink protector pattern was evidenced on a few of the panels. Therefore, according to the technical data sheet, the panels were retreated again. It was determined that when the panels were turned over to rinse the opposite sides, that the clean side was found to come into direct contact with acid-gel-contaminated surfaces left behind on the sink protector. This time, very careful attention was paid not to recontaminate the initial clean sides. Prior to shipment to the laboratory, the panels were vacuum-packed using a food saver. This way, the excellent condition of the cleaned panels was preserved during shipping.

Lining Application

Coating 1 was applied in three coats while Coating 2 was applied in a single coat. Both Coating 1 and Coating 2 were applied in accordance with the lining manufacturer’s instructions to the three sets of panels; Set A, Set B and Set C. Figure 3 shows examples of the coated panels. The same applicator who performed the abrasive blasting of the steel panels undertook the coating application.

Table 2: Coating 2 Autoclave Analysis

|

149 C, 250 psig, 10% H2S, 10% CO2, 80% CH4, Sour Crude, 5% NaCl in Distilled Water, 96 hrs. |

Coating

1 |

Avg.

DFT |

Adhesion Rating

(ASTM D6677) |

Blistering

(ASTM D714) |

Impedance (log Z @ 0.1 Hz)

(ASTM D6677) |

|

Pre-Test |

Water |

HC |

Gas |

Water |

HC |

Gas |

Pre-Test |

Water |

HC |

Gas |

|

1A |

21.1 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

N |

N |

N |

9.96 |

7.07 |

10.68 |

10.49 |

|

2A |

21.0 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

N |

N |

N |

6.98 |

7.19 |

6.98 |

|

1B |

24.5 |

8 |

8 |

4 |

6 |

N |

N |

N |

10.04 |

7.44 |

10.57 |

10.28 |

|

2B |

24.5 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

N |

N |

N |

7.50 |

10.29 |

10.58 |

|

1C |

16.7 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

N |

N |

N |

10.28 |

6.54 |

10.05 |

10.01 |

|

2C |

17.4 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

N |

N |

N |

7.45 |

10.11 |

10.60 |

-

DFTs were measured for each coating and each phase. Average DFT reported.

-

HC = hydrocarbon.

-

Panels A – Applied to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 abrasive blasted steel.

-

Panels B – Applied to panels above which were then deliberately contaminated with gaseous H2S (10%) and NaCl solution (5%), washed with tap water and brush blasted on one side.

-

Panels C – Applied to Panels B treated with the chemical cleaner.

Table 3: Conductivity and Surface Profile Measurements

of Test Panels Pre-Coating Application

|

Test Panel from Set |

General Characteristics

and Comments |

Total Dissolved Salts (TDS) |

Average Surface Profile (mils) |

A: No contamination

abrasive blast |

SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1

white metal blast standard |

0 μS/cm |

2.63 (1st panel)

2.50 (2nd panel) |

B: Deliberate contamination, washed*,

not re-swept |

Black surface: uniform rusting throughout

(FeS/iron oxide) |

32 μS/cm |

N/A |

B: Deliberate contamination unwashed,

not re-swept |

Black surface: uniform rusting throughout

(FeS/iron oxide) |

14 μS/cm |

N/A |

C: Chemical treatment to a

Panel B that was washed |

SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white

metal blast standard |

0 μS/cm |

3.63 (1st panel)

3.53 (2nd panel) |

*The washed Panel B was cleaned with low-pressure water washing at 3,500 psi with Alberta tap water that had a conductivity of 348μS/cm (chloride, sulfate and nitrate concentrations of 4, 65 and 0 ppm)

Test Methods for Coating Evaluation

Autoclave

The primary screening test most commonly employed by facility owners in the oil patch for tank and vessel linings is NACE TM0185, “Evaluation of Internal Plastic Coatings for Corrosion Control of Tubular Goods by Autoclave Testing.”14 The test environment consisted of three phases: a gas phase mixture of 10-percent H2S, 10-percent CO2, 80-percent CH4, a hydrocarbon phase of sour crude, and an aqueous phase of a 5-percent NaCl solution. The tests were conducted at 149 C and at a total pressure of 250 psig. The test temperature had an accuracy of plus or minus 3 degrees C.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS was used as a diagnostic tool to compare barrier properties before and after autoclave exposure. Essentially, the low frequency impedance (AC electrical resistance) is related to the permeability of the coating to water, organic molecules and small gaseous molecules such as H2S and CO2. The log Z value, where Z is impedance at 0.01 Hz is typically used as the basis for comparison of a coating’s barrier properties15, 16. The higher the impedance of a coating, the higher barrier properties it has, thus the more protective the coating is. A basic rule of thumb is that the barrier performance of a coating is excellent, good or marginal when log Z values are on the order of 10, 8 and 6; respectively.

Adhesion and Visual Rating

After the coating panels were removed from the autoclave they were evaluated visually for any defects such as blistering per ASTM D71417 or cracking. The coatings’ adhesion was also assessed per ASTM D667718 and the DFT was measured. The pre- and post-test adhesion of each coating was rated according to ASTM D6677.

Surface Profile Measurements

Surface profile measurements were performed using high-temperature, extra-course replica tape. Three measurements were taken on each sample. No surface profile measurements were carried out on panels that had heavy black iron sulfide deposits.

Conductivity Measurements

The retrieval of total dissolved salts (TDS) and analysis of conductivity were carried out in accordance with SSPC-Guide 1519. A 500-milliliter liquid reagent sample was retrieved from each steel panel using the laboratory boiling extraction method. The TDS conductivity analysis was performed using a probe-type conductivity meter. The conductivity and pH measurements were taken with a cooled to room temperature sample (25 C [77 F]) instrument with temperature-compensation capability.

SEM-EDX

The SEM is capable of examination of surfaces with enhanced depth of field up to magnifications of 250,000 times. The EDX analysis system detects elemental composition from very light elements such as carbon, to heavy elements such as lead. The instrument was used to evaluate the surface of the panels to characterize the surface profile and detect the elemental composition present at the surface. The depth of beam penetration was approximately 5 µm. One limitation of this analysis is that it will not determine the compounds present. Various forms of iron oxide exist, for example FeO, FE2O3 and FE3O4, however, these would only be characterized as iron and oxygen.

X-Ray Diffraction

The X-ray diffraction system was utilized to further characterize the crystallographic phase of compounds present on the surface. The depth of beam penetration for this method was approximately 10 µm. X-ray diffraction will differentiate between crystallographic compounds such as the aforementioned FeO, FE2O3 and FE3O4, or Fe (OH)2. Analysis was performed on the surface of test panels in Sets B and C.

Results and Discussion

The results of the autoclave testing of Coating 1 and Coating 2 at 149 C in sour crude are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

In Table 1, 1A refers to the front side of a given panel from the A panel set, whereas 2A refers to the back side of the same panel. The entire panel was coated with Coating 1. The same applies to panels B and C.

In Table 2, 1A refers to the front side of a panel from the A set, and once again, 2A refers to the back side of the same A panel with the entire panel coated with Coating 2, and the same for panels B and C.

Post-autoclave test panels are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Figure 6 provides a comparison of pre- and post-test impedance values.

A coating was deemed to have failed in the autoclave test if it blistered, cracked or flaked in any of the three phases. Adhesion ratings of the coating film were considered of lower importance than the presence, or absence, of film blistering. Coatings may provide sufficient adhesion and sub-film corrosion resistance even when water has been imbibed and reached the coating-metal interface.

The solvent-borne Coating 1 showed no blistering in all phases regardless of panel type, with the exception for panel 2B which showed F#2-sized blisters in the water phase. Coating 1 maintained or in many cases improved its adhesion rating compared to its pre-test condition. The coating showed excellent pre-test impedance and maintained high log Z of greater than 10 values post-test in the gas and hydrocarbon phases. However, these values decreased in the water phase to log Z of 7-to-8 indicative of the more aggressive water phase.

Inspection of the EIS values shows that the performance of Coating 1 slightly improved in the gas phase on chemically treated Set C panel surfaces compared to Set A and Set B panel surfaces.

In earlier studies, the performance of Coating 1 at 149 C was excellent when applied to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal blasted surface that had been post treated with the chemical cleaner and subject to a surface decontamination process; the performance of Coating 1 at 149 C was very poor when applied to a surface prepared to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 standard but not post-treated with the chemical cleaner10. In the present study, however, the performance of Coating 1 under similar conditions was very good on both types of surfaces. This result indicates that a certain inconsistency of coating performance arises on steel that has been prepared to a white metal standard alone. This is not surprising since the appearance of a white metal surface does not signify the absence of residual soluble or insoluble moieties, nor detrital materials.

The solvent-free Coating 2 had as high pre-test impedance values as did Coating 1 and showed similar post-test impedance behavior. With Coating 2 on white metal Set A panel surfaces there was an inconsistency of EIS values not seen on the chemically cleaned Set C panels. Adhesion of Coating 2 on Set B panels decreased significantly in all phases when compared to panels from sets A and C which maintained, or slightly changed, vis-à-vis adhesion rating. Overall, the adhesion ratings of Coating 2 were lower than Coating 1 indicating superior wetting out of the solvent-borne Coating 1. Interestingly, the adhesion ratings for Coating 2 improved significantly in the gas phase on the chemically prepared Set C panel surfaces.

The adhesion of Coating 2 was significantly improved on Set C panel surfaces versus Set B panel surfaces. This showed that the chemical cleaner had performed well in achieving a contaminant-free surface, removing both soluble and insoluble moieties. In the case of Set C panels with the chemical cleaner treatment, as evidenced by the log Z values, the excellent barrier performance was consistent on both panel sides (Table 2). However, in the case of Set A panels with only the SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 abrasive blast, there was good barrier performance on one side of the panel but poor performance on the other side. Hence, as seen in our earlier studies, the efficacy of the chemical treatment appears to lead to an increasing consistency of superior performance when using the cleaner as a complementary (and to re-iterate, arguably necessary) treatment for the abrasive blast-cleaning prior to coating application.

The chemical treatment improved the adhesion of the solvent-free Coating 2 on decontaminated steel, compared to the Coating 2 adhesion on either SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal or contaminated, power washed and white metal surfaces that were subsequently brush-blasted (Table 2).

Surface Profile Measurement and Visual Observations

As shown in Table 3, the surface profile of two panels that were abrasive blasted to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal standard averaged 2.63 mils for the first panel, and 2.50 mils for the second panel. In marked contrast, the surface profile of two panels that were abrasive blasted to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal, contaminated in the autoclave prior to a low-pressure water wash at 3,500 psi, and then given the chemical cleaner treatment, averaged 3.63 mils for the first panel and 3.53 mils for the second panel. This increase in profile depth occurred as a result of the corrosion of the steel in the autoclave since, in separate work, the cleaner itself was shown not to increase the profile depth on bare steel panels abrasive blasted to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1. Application of the cleaner and its subsequent neutralization and removal with low-pressure washing removed all abrasive media embedment on a panel from Set C (whereas the abrasive-blasted white metal panel from Set A was full of embedment). The removal of embedded detrital material was not achieved by pressure washing alone.

The abrasive-blasted surface that was cleaned to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1, and subsequently treated with the chemical cleaner, evidenced a cleaner looking surface and a dull matte pewter color (Fig. 7). Interestingly, in the mid-1980s, an abrasive-blasted surface also cleaned to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 by ultra-high pressure (UHP) water jetting at 140 Mpa evidenced a dull matte bluish-golden color (thought at the time to be a thin film of a coherent metal oxide layer)20.

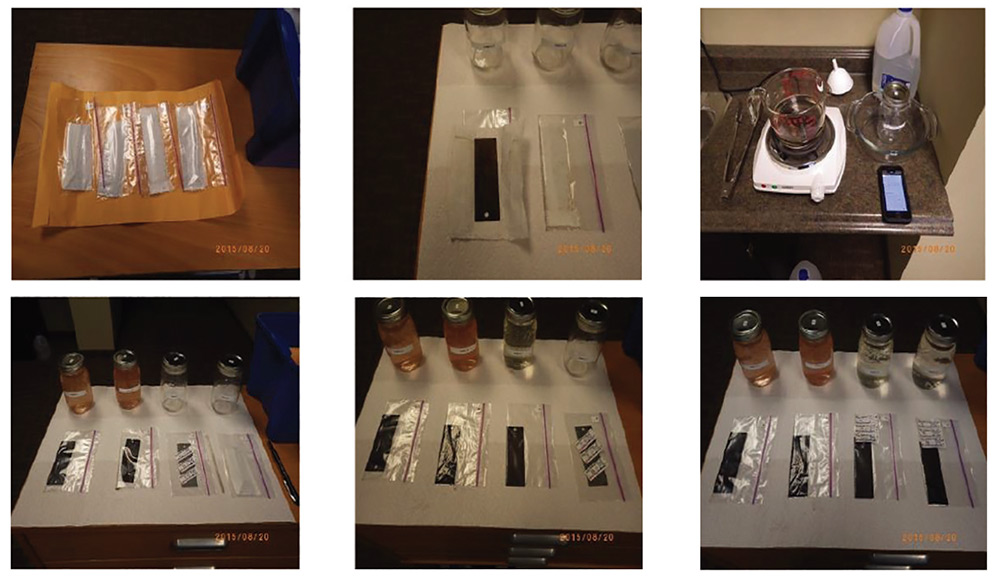

Conductivity Measurements

An uncontaminated panel from Set A and a chemically treated panel from Set C had conductivity measurements of 0 µS/cm (Table 3). The unwashed and deliberately contaminated panel had a conductivity of 14 µS/cm. The deliberately contaminated panel that was low-pressure washed at 3,500 psi with Alberta tap water had a conductivity of 32 µS/cm. Hence, the conductivity of the tap water was questioned. This tap water was later determined to have a conductivity of 348 µS/cm, with chloride, sulfate and nitrate concentrations of 4, 65 and 0 ppm, respectively. Figure 8 shows laboratory and test panel conditions prior to conducting conductivity and surface profile measurements.

It is important to note that per the manufacturer’s stipulation to achieve proper chemical decontamination, in the present study, only deionized water should be used (and indeed was used) to prepare the Step 1 cleaner solution and the Step 2 wash solution. The efficacy of this two-step cleaning process is not based on the application of corrosion inhibitors where inhibitor moieties are intentionally left on the steel surface and can affect the performance of the coating. Rather, this system is designed to clean the steel surface without leaving any chemicals which can interfere with the coating performance or participate in corrosion.

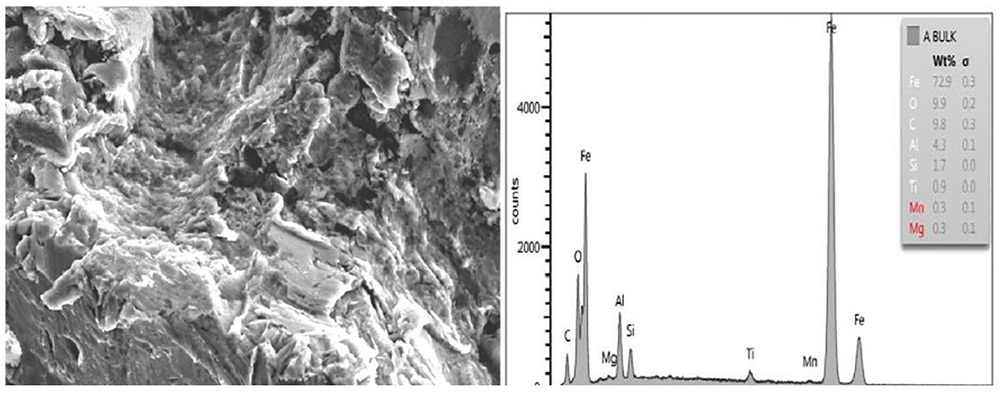

SEM-EDX

Investigations were carried on the uncoated panels shown in Figure 7. A bulk surface analysis performed with EDX indicated the presence of iron, oxygen and carbon with aluminum, silicon and titanium, suspected oxides from the embedded blasting media. The initial examination revealed surface contamination versus the metal surface more clearly. Secondary electron imaging was then performed at the same magnifications (50, 200 and 400 times magnification) to compare the surfaces of all three panels.

Fig. 7: (Left) Panel A, Panel B (washed, brush blasted one side; contaminated on other side) and Panel C. (Center) Panel A, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and (Right) Panel C, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and chemically cleaned.

Fig. 7: (Left) Panel A, Panel B (washed, brush blasted one side; contaminated on other side) and Panel C. (Center) Panel A, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and (Right) Panel C, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and chemically cleaned.

Fig. 8: (Top row, Left) Test panels as received, (Center) unpacking of Test Panel B washed, uniform rusting throughout; Test Panel B unwashed similar and (Right) Test Panel B, boiling extraction method, all others similar. (Bottom row, Left): Test Panel A, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction, (Center) Test Panel C, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction and (Right) Liquid reagent sample cooling and test panels repackaged after boil extraction. Photos courtesy of Norske Corrosion and Inspection Services Ltd.

Fig. 8: (Top row, Left) Test panels as received, (Center) unpacking of Test Panel B washed, uniform rusting throughout; Test Panel B unwashed similar and (Right) Test Panel B, boiling extraction method, all others similar. (Bottom row, Left): Test Panel A, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction, (Center) Test Panel C, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction and (Right) Liquid reagent sample cooling and test panels repackaged after boil extraction. Photos courtesy of Norske Corrosion and Inspection Services Ltd.

For the panels from Set A blasted to SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and the post abrasive-blast chemically treated panel from Set C, much higher magnification was employed to evaluate and compare the arresting features found on the latter’s surface. Magnifications of 1,000, 2,000, 4,000, 8,000 and 15,000 times magnification were utilized. It was learned after the analysis that a latent carbon peak exists, which places a small carbon peak in all EDX printouts. Notable findings from SEM and EDX analysis were as follows.

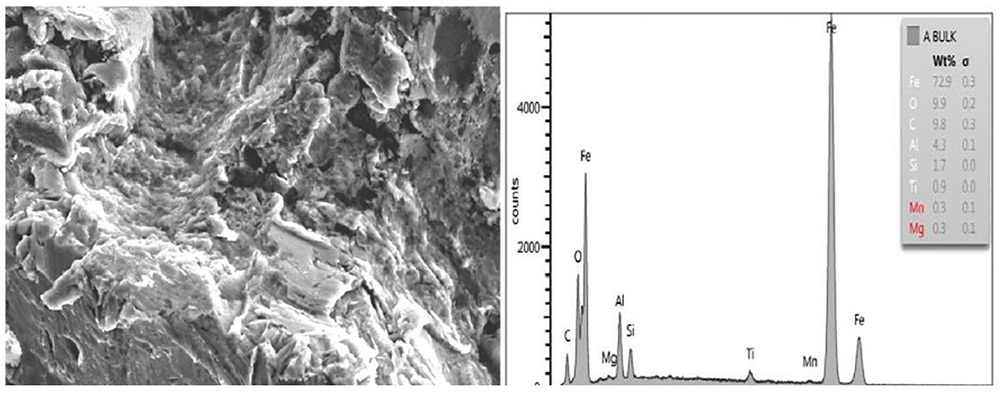

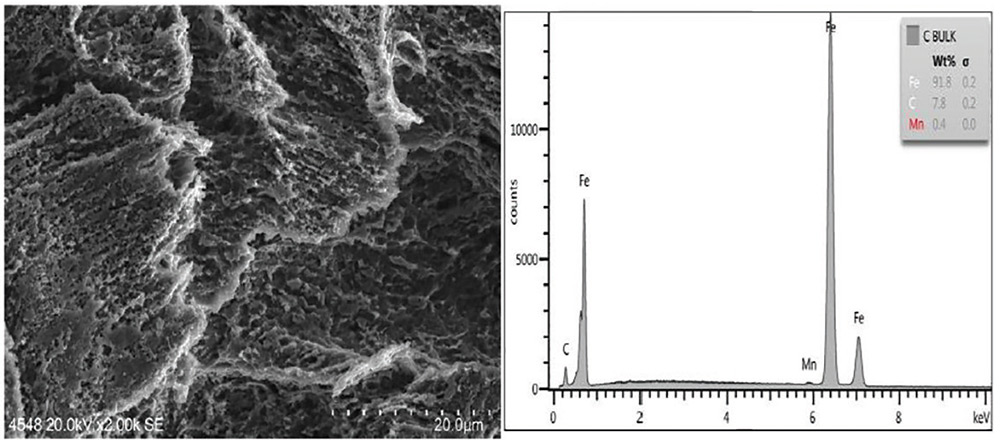

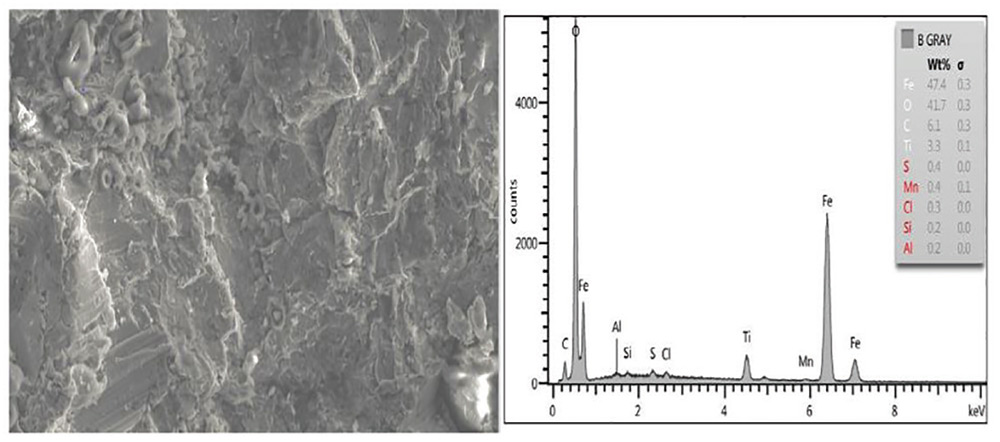

Residual oxides, sulfides and embedment of abrasive media were clearly seen on the SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 blast-cleaned surface of Set A panels (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9: SEM image of Panel A (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDXA) elemental analysis showing iron, oxygen and other elements.

Fig. 9: SEM image of Panel A (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDXA) elemental analysis showing iron, oxygen and other elements.

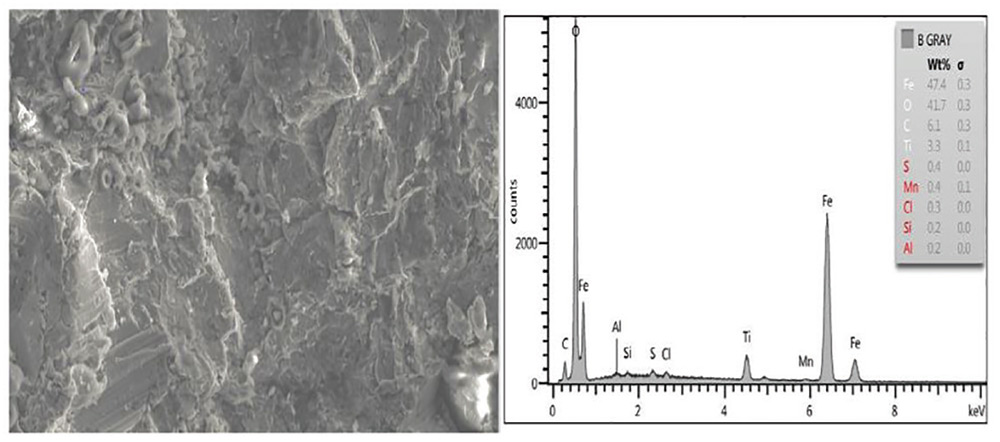

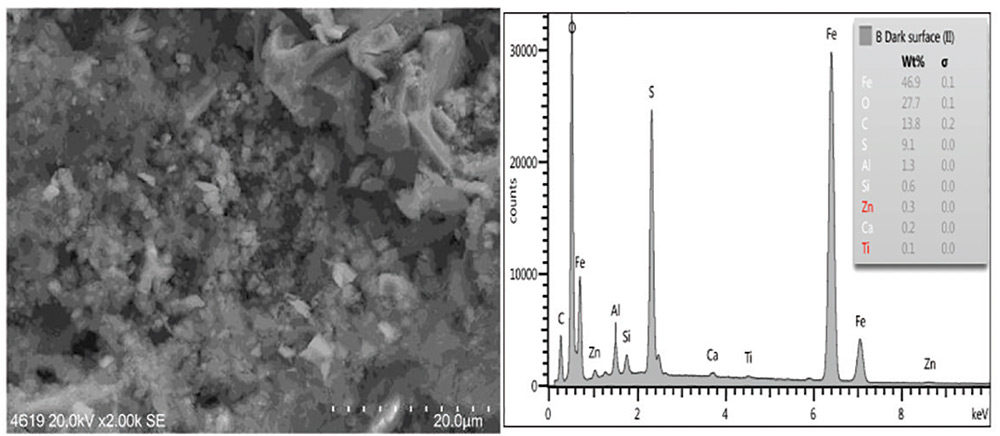

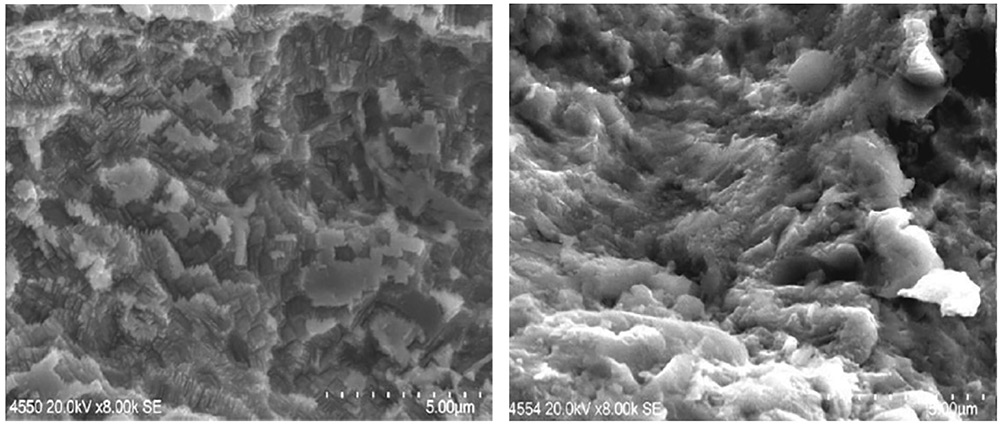

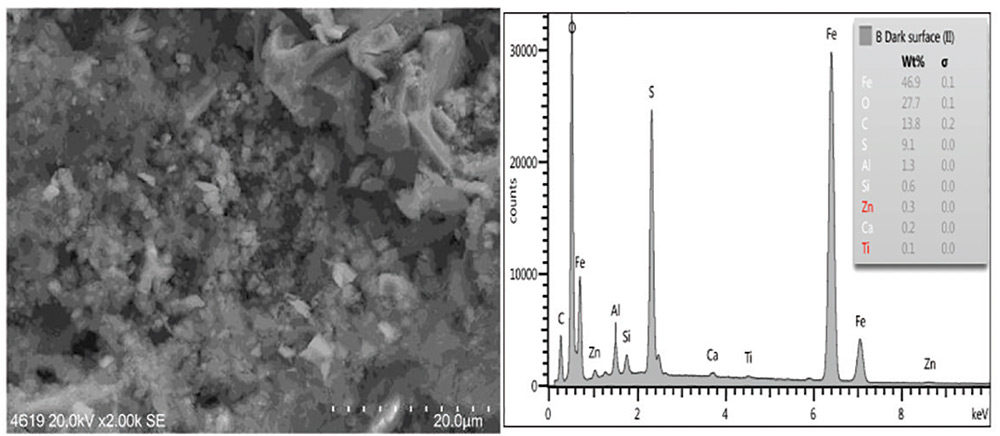

Residual oxides and sulfides were present on a panel from Set B, especially the back surface which also exhibited a dark surface with a visible cross-hatch pattern (panels were placed on a grid). The amount of surface oxide and sulfide constituents was greatest on this sample (Figs. 10 and 11).

Fig. 10: SEM image of Panel B clean surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron oxide and other elements.

Fig. 10: SEM image of Panel B clean surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron oxide and other elements.

Fig. 11: SEM image of Panel B dark surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron sulfide and iron carbonate (as per XRD analysis).

Fig. 11: SEM image of Panel B dark surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron sulfide and iron carbonate (as per XRD analysis).

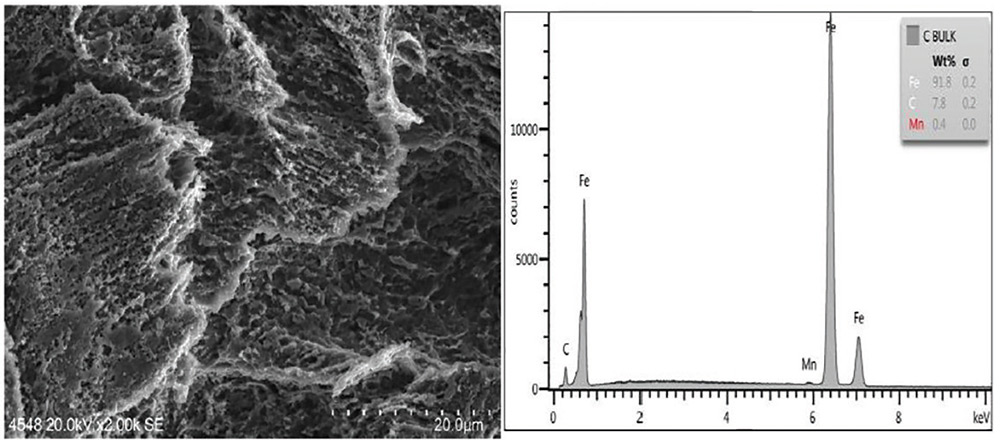

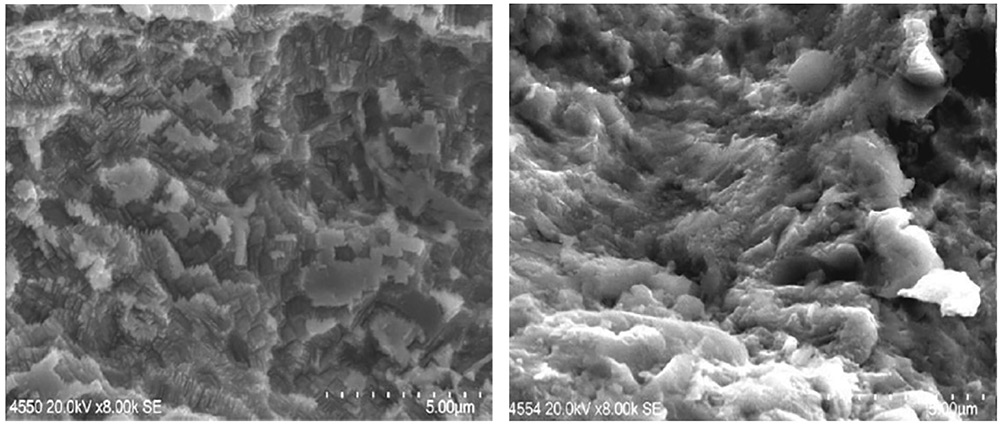

The post abrasive-blast (SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1), water-washed and chemically treated surface of a panel from Set C was extremely clean and as shown in Figures 12 and 13 evidenced a uniformly etched surface with greater angularity and profile depth compared to the blasted and water-washed surface of panels from Set B. These features accord well with a) the greater profile depth of panels from Set C versus panels from Set B when measured with coarse replica tape, b) a difficulty observed in removing the replica tape on panels from Set C, and c) the snagging of a rubber glove when moved across a panel from Set C but not when moved across panels from Sets A or B. This profile difference is a direct result of the corrosion of the abrasive-blasted steel in autoclave conditions and not due to the cleaner treatment itself.

Fig. 12: SEM image of Panel C (2,000 times as taken) showing etched surface from exposure to corrosive environment subsequently treated with cleaner. Surface is clean as shown by the predominantly iron peak shown in the EDX analysis.

Fig. 12: SEM image of Panel C (2,000 times as taken) showing etched surface from exposure to corrosive environment subsequently treated with cleaner. Surface is clean as shown by the predominantly iron peak shown in the EDX analysis.

Fig. 13: (Left) At 8,000 times magnification, the surface of Panel A as blasted and (Right) Panel C after chemical treatment. Panel C shows etching effect from exposure to corrosive environment. By removing all the contaminants the chemical cleaner system has revealed the surface topography.

Fig. 13: (Left) At 8,000 times magnification, the surface of Panel A as blasted and (Right) Panel C after chemical treatment. Panel C shows etching effect from exposure to corrosive environment. By removing all the contaminants the chemical cleaner system has revealed the surface topography.

Embedded alumina and silica were observed in the white metal blasted surface of panels from Set A and to a lesser degree on panels from Set B, and a significant oxygen and carbon peak when the surfaces were analyzed at very low kilovolts (kV). The lower accelerating voltage of 5 kV results in less beam penetration and facilitates enhanced analysis of light elements compared with analyses made at 20 kV. Panels from Set C exhibited virtually no evidence of embedded material, surface oxide or any contamination of sulfur, chloride or oxygen, or indeed any other contamination. When the analysis is run at low kV, one essentially observes the iron L peak, and a small carbon peak, compared with the white-metal-blasted surface which exhibits a much higher carbon, oxygen peak and their ratio to the iron L peak.

Analysis by X-ray diffraction (XRD) was carried out in order to further evaluate the surface of a panel from Set C and to compare with the pre-chemically cleaned surface of a panel from Set B. It was suspected that the surface of the Set C panel must have some thin surface coating, possibly iron carbonate, or iron oxide present, which are both crystallographic and would be detected and characterized by XRD. Comparison surfaces were also analyzed, the relatively clean front surface of the Set B panel, and the unique dark patterned surface on the back of the panel labeled B2. The results of the XRD analysis are shown in Table 4 and summarized as follows.

Sample B, the clean side of panel B, consisted of 94 percent (by weight) iron with 5.3 percent embedded abrasive blast media in the form of alumina and silica.

Sample C, the chemically treated surface of panel C, consisted of 99.4 percent iron (from the steel substrate), 0.3 percent iron phosphate, 0.1 percent calcium carbonate, 0.1 percent silicon oxide and 0.1 percent manganese based oxide.

Sample B2, the back surface of panel B, consisted of 53.5 percent iron (II) carbonate, 36.4 percent iron (II) sulfide, 4.1 percent zinc sulfide, 1.4 percent silicon oxide, 2.3 percent iron and other trace compounds.

Sample C2, the back surface of panel C, consisted of 96.6 percent iron, 0.3 percent silicon oxide, 0.8 percent iron carbonate, 1.3 percent iron (II) sulfide, 0.4 percent iron phosphide, 0.4 percent calcium carbonate and 0.2 percent magnetite (FE3O4).

The results from XRD confirm the findings of the EDX analysis. The chemically cleaned pewter-colored panel shows significant cleaning with negligible surface film, no sulfide deposits, no carbonate deposits or any apparent oxide formation (Fig. 13). Both EDX and XRD penetrate the surface somewhat, and there is a possibility that a very thin surface film may be present that is not detectible using these techniques. It is speculated that the surface is not passivated per se, in terms of a protective oxide layer, but to be in a passive state given that it appears to essentially consist of pure iron (Fig. 12).

Also of significance, is that the back surface of panel B, which exhibited a large amount of surface contamination, was essentially a bare steel substrate after the chemical cleaning process. The surface was approximately 97-percent iron after cleaning, with small concentrations of other crystallographic constituents present.

Conclusions

High-temperature 149 C autoclave studies were conducted on a multi-coat, solvent-borne, epoxy novolac system (Coating 1) and a thick-film single-coat solvent-free polycyclamine-cured hybrid epoxy coating (Coating 2). The lining performance on steel panels subject to the chemical cleaner decontamination procedure after first abrasive blasting to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal standard is equal to (or marginally superior in the case of Coating 2) the performance observed on steel prepared to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal standard.

The chemical treatment afforded discernible performance increments in terms of adhesion for the increasingly popular solvent-free coating, Coating 2.

Based on conductivity measurements, abrasive blasting to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal standard showed no difference between coated panels tested with or without the chemical decontamination procedure. The efficacy of the proprietary cleaner used as a means to decontaminate abrasive-blasted steel was clearly demonstrated in the SEM-EDX and XRD studies. The cleaner was not deleterious to the carbon-steel substrate even during extended surface contact of the cleaner with steel as tested. It readily removed ample amounts of insoluble iron sulfide species, iron carbonate and iron oxide from the substrate.

Comparing the results of this work and earlier work by the authors, a certain inconsistency of coating performance has been noted on steel that has been prepared to an SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 white metal standard. This reflects the fact that the white metal standard does not signify the absence of residual soluble or insoluble moieties, nor detrital materials.

Now for the answers to questions posed at the outset of this study. First, some of the autoclave, EIS and adhesion trends seen in previous studies were not repeated in this work. The cleaner did demonstrate an advantage using the post-abrasive-blast applied treatment to enhance the adhesion of the Coating 2 solvent-free system, but not the Coating 1 solvent-borne system. Second, the cleaner decontaminated the carbon steel surface and removed both non-visible (and ample amounts of visible) iron sulfide, iron carbonate, iron oxides and soluble salt contaminants. Third, the cleaner afforded a passive state surface (perhaps as opposed to passivation vis-à-vis an oxide layer) of iron alone on the carbon steel. Further studies are underway on characterizing the surface. Fourth, the cleaner did not show any evidence of etching the steel surface.

Is there such a thing as “blind chance”? For those true fans of Russian roulette, we are sorry that we cheated and unloaded the gun! Yes, the answer to question 5 was indeed affirmative: the cleaner did unload the gun. The question remains: will industry unload the gun or continue to get shot by anomalies? JPCL

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express sincere appreciation to the following for their considerable assistance in this work.

Park Derochie, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada for preparing the steel panels and the coating application.

Norske Corrosion & Inspection Services, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada for conductivity and surface profile measurements.

Travis Gafka, International Paint LLC, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada for panel preparation and field inspections.

Bob Tucker, Stone Tucker Instruments Inc. Edmonton, Alberta, Canada for surface profile analyses.

This article is published with permission from NACE International.

About the Authors

|

|

Yasir Idlibi of MICHAL Consulting has over 15 years of experience in protective coatings research and development and global marketing, as well as sales and business development. |

|

|

Jason Hartt is the laboratory manager at ADANAC Global Testing & Inspection and has worked there since its inception in 2012. Hartt has nine years of coating testing experience in the protective coatings industry. |

|

|

Mike O’Donoghue is the director of engineering and technical services for International Paint LLC. He has 34 years of experience in the marine and protective coatings industry. |

|

|

Vijay Datta is the director of industrial maintenance for International Paint LLC. He has 48 years of experience in the marine and protective coatings industry. |

|

|

Bill Johnson, AScT, is the manager of laboratory services with Acuren Group Inc., in Richmond, British Columbia. Johnson has more than 20 years of experience in materials testing, failure analysis, scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray analysis. |

References

-

O’Donoghue M, Datta V.J. and Spotten R. “Angels and Demons in the Realm of the Underworld of VOCs,” JPCL, April, 2011, pp.14-29.

-

Tinklenberg G. and Allen J.R. “Anchor Pattern: What’s Best,” publication provided to the authors, pp. 62-80.

-

Ward D. “An Investigation into the Effect of Surface Profile on the Performance of Coatings in Accelerated Corrosion Tests,” NACE Corrosion 2007 Conference and Expo.

-

Roper H.J., Weaver R.E.F. and Brandon J.H. “The Effect of Peak Count on Surface Roughness on Coating Performance,” JPCL, June, 2005, pp. 52, 62, 63.

-

Schilling M.S. “Soluble Salt Frenzy-Junk Science: Part I,” Corrosion and Materials, ACA, Vol. 31, No.5, 2006, pp. 1015.

-

Tator K.B. “Soluble Salts and Coatings – An Overview,” JPCL, February, 2010, pp. 5-63.

-

Mitschke H. “Effects of Chloride Contamination on the Performance of Tank and Vessel Linings,” JPCL, March, 2001, pp. 49-56.

-

Ault J.P. and Ellor J.A. “Painting Over Flash Rust and Other Surface Contaminants,” TRI-Service 2007 (Denver, Colo, NACE) p. 1, 2007.

-

Zheng Y, Ning J., Brown B., Young D., Nesic S. “Mechanistic Study of the Effect of Iron Sulfide Layers on Hydrogen Sulfide Corrosion of Carbon Steel,” NACE International Corrosion Conference and Expo 2015, Houston, Texas.

-

O’Donoghue M. and Datta V.J. “Old, New and Forgotten Wisdom for Tanks and Vessel Linings,” presented at SSPC National Conference, Lake Buena Vista, Florida, February, 2014.

-

Melancon M., Hourcade S. and Al-Borno, A. “The Effect of Four Commercially Available Steel Decontamination Processes on the Performance of External Coatings,” Corrosion, March, 2014, pp. 1-15.

-

Melancon M., Hourcade S., Al-Borno A., Liskiewicz T., Cortes J. and Chen X. “The Effect of Four Commercially Available Decontamination Processes on the Performance of Internal Linings,” SSPC Conference Proceedings, February, 2015.

-

Bock P. and Crain R. “Removal of Bound Ions from Carbon Steel Surfaces,” NACE 2015 Corrosion Conference and Expo.

-

NACE TM0185-2006, “Evaluation of Internal Plastic Coatings for Corrosion Control of Tubular Goods by Autoclave Testing,” NACE International, Houston, Texas.

-

Gray L.G.S., Danysh M.J., Prinsloo H., Steblyk R. and Erickson L. “Application of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Evaluation of Protective Organic Coatings in Field Inspections,” Presented at NACE Northern Area Regional Conference, Calgary, Alberta, March, 1999.

-

Gray L.G.S. and Appleman B.R. “EIS: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy A Tool to Predict Remaining Coating Life?” JPCL, Vol. 20 (2), pp. 66, 2003.

-

ASTM D714 (latest revision), “Standard Test Method for Evaluating Degree of Blistering of Paints,” ASTM, West Conshohocken, Pa.

-

ASTM D6677 (latest revision), “Standard Test Method for Evaluating Adhesion by Knife,” ASTM, West Conshohocken, Pa.

-

SSPC-Guide 15 (latest revision), “Field Methods for Extraction and Analysis of Soluble Salts on Steel and Other Nonporous Substrates,” Pittsburgh, Pa.

-

Frenzel L., “How Does Waterjet Cleaning Affect the Surface and Surface Preparation?” Ultra-High Pressure Water Jetting, JPCL, January, 2010, pp. 44-55.

Fig. 2: Examples of deliberately contaminated panels.

Fig. 2: Examples of deliberately contaminated panels. Fig. 3: Examples of pre-test panels. (Left to right): Coating 2-Panel A, Coating 1-Panel B, Coating 2-Panel B and Coating 1-Panel C.

Fig. 3: Examples of pre-test panels. (Left to right): Coating 2-Panel A, Coating 1-Panel B, Coating 2-Panel B and Coating 1-Panel C. Fig. 4: Coating 1 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C.

Fig. 4: Coating 1 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C.

Fig. 5: Coating 2 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C.

Fig. 5: Coating 2 panels, post autoclave test. (Left to right): 2A, 1B, 2B and 1C. Fig. 6: Impedance, pre- and post-autoclave exposure.

Fig. 6: Impedance, pre- and post-autoclave exposure. Fig. 7: (Left) Panel A, Panel B (washed, brush blasted one side; contaminated on other side) and Panel C. (Center) Panel A, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and (Right) Panel C, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and chemically cleaned.

Fig. 7: (Left) Panel A, Panel B (washed, brush blasted one side; contaminated on other side) and Panel C. (Center) Panel A, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and (Right) Panel C, SSPC-SP 5/NACE No. 1 and chemically cleaned. Fig. 8: (Top row, Left) Test panels as received, (Center) unpacking of Test Panel B washed, uniform rusting throughout; Test Panel B unwashed similar and (Right) Test Panel B, boiling extraction method, all others similar. (Bottom row, Left): Test Panel A, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction, (Center) Test Panel C, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction and (Right) Liquid reagent sample cooling and test panels repackaged after boil extraction. Photos courtesy of Norske Corrosion and Inspection Services Ltd.

Fig. 8: (Top row, Left) Test panels as received, (Center) unpacking of Test Panel B washed, uniform rusting throughout; Test Panel B unwashed similar and (Right) Test Panel B, boiling extraction method, all others similar. (Bottom row, Left): Test Panel A, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction, (Center) Test Panel C, surface profile measurements (ASTM D4417) prior to boil extraction and (Right) Liquid reagent sample cooling and test panels repackaged after boil extraction. Photos courtesy of Norske Corrosion and Inspection Services Ltd. Fig. 9: SEM image of Panel A (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDXA) elemental analysis showing iron, oxygen and other elements.

Fig. 9: SEM image of Panel A (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDXA) elemental analysis showing iron, oxygen and other elements. Fig. 10: SEM image of Panel B clean surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron oxide and other elements.

Fig. 10: SEM image of Panel B clean surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron oxide and other elements. Fig. 11: SEM image of Panel B dark surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron sulfide and iron carbonate (as per XRD analysis).

Fig. 11: SEM image of Panel B dark surface (2,000 times as taken) showing surface and bulk EDXA elemental analysis showing iron sulfide and iron carbonate (as per XRD analysis). Fig. 12: SEM image of Panel C (2,000 times as taken) showing etched surface from exposure to corrosive environment subsequently treated with cleaner. Surface is clean as shown by the predominantly iron peak shown in the EDX analysis.

Fig. 12: SEM image of Panel C (2,000 times as taken) showing etched surface from exposure to corrosive environment subsequently treated with cleaner. Surface is clean as shown by the predominantly iron peak shown in the EDX analysis. Fig. 13: (Left) At 8,000 times magnification, the surface of Panel A as blasted and (Right) Panel C after chemical treatment. Panel C shows etching effect from exposure to corrosive environment. By removing all the contaminants the chemical cleaner system has revealed the surface topography.

Fig. 13: (Left) At 8,000 times magnification, the surface of Panel A as blasted and (Right) Panel C after chemical treatment. Panel C shows etching effect from exposure to corrosive environment. By removing all the contaminants the chemical cleaner system has revealed the surface topography.