FRIDAY, JANUARY 22, 2021

A team of researchers from the Oregon State University’s College of Engineering have recently conducted a study using supercomputer simulations to observe how chloride causes corrosion and degrades iron.

“Steels are the most widely used structural metals in the world and their corrosion has severe economic, environmental and social implications,” said study co-author Burkan Isgor, an OSU civil and construction engineering professor. “Understanding the process of how protective passive films break down helps us custom design effective alloys and corrosion inhibitors that can increase the service life of structures that are exposed to chloride attacks.”

The Study

Using high-performance computers at the San Diego Supercomputer Center and the Texas Advanced Computing Center, Isgor, alongside OSU School of Engineering colleague Líney Árnadóttir and graduate students Hossein DorMohammadi and Qin Pang, were able to utilize computational methods to observe chloride’s role in iron’s degradation.

“For this study we relied on allocations from the National Science Foundation’s Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment so that we could use Comet and Stampede2 to combine different computational analyses and experiments applying fundamental physics and chemistry approaches to an applied problem with potentially great societal impact,” said Árnadóttir.

|

| Oregon State University College of Engineering |

|

A team of researchers from the Oregon State University’s College of Engineering have recently conducted a study using supercomputer simulations to observe how chloride causes corrosion and degrades iron. |

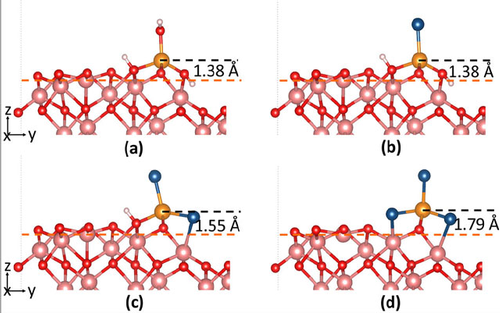

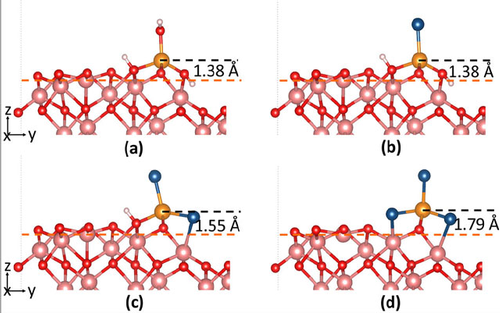

According to UC San Diego, the research team proposed a four-stage depassivation mechanism based on reactive force field molecular dynamic simulations using a method called density functional theory to investigate the structural, magnetic and electronic properties of the molecules involved in chloride’s corrosion process.

These simulations, however, were also supported by using reactive molecular dynamics, which allowed the team to accurately model the chemistry-based nanoscale processes that lead to chloride-induced breakdown of iron passive films.

“Modeling degradation of oxide films in complex environments is computationally very expensive, and can be impractical even on a small local cluster,” said Isgor. “Not only do Comet and Stampede2 make it possible to work on more complex, more realistic, and industrially relevant problems, but also these high-performance computers let us do so within a reasonable timeframe, moving knowledge forward.”

Through their combined efforts, the team found that the four surface species, formed in the four stages, had decreasing surface stability and was consistent with the order of species formed in the depassivation process.

Written in the study’s abstract, “The Fe vacancy formation energy, that is the energy needed to form a surface Fe vacancy by removing different surface species, indicates that surface species with more chlorides dissolve more easily from the surface, suggesting that chloride acts as catalyst in the iron dissolution process. The results are consistent with the suggested four-stage reaction mechanism and the point defect model.”

The study was published in a Nature partner journal, Materials Degradation. This work was supported by the NSF, CMMI (1435417). Part of the calculations used XSEDE (TG-ENG170002, TG-DMR160093), which is supported by NSF (ACI-1053575).

Tagged categories: Chlorides; Chlorides; Chlorine-induced corrosion; Colleges and Universities; Corrosion; Corrosion engineering; Quality Control; Research and development