How Salt Shippers Can Beat a Shortage of End-Of-Life Rail Cars

From JPCL May/June 2024

By Matthew McDonald, Carboline

Photos: (from left) andy sotiriou / getty images; john coletti / getty images

Bulk salt shippers across North America have a problem. A shortage of the hopper cars that comprise the continent’s salt car fleet is threatening to disrupt the consistent, reliable and cost-effective transportation of the commodity. It’s not just any shortage, because salt shippers do not transport their freight in just any hopper cars. Instead, they rely almost exclusively on old rolling stock nearing the end of its useful life. But a shortage of those assets means either the shippers must be ready to adjust to the scarcity, or embrace a new way of thinking about how salt is shipped over the rails.

Fig. 1: The exterior of this hopper car is protected by a single coat of direct-to-metal (DTM) epoxy. This widespread corrosion is typical of rail cars in salt service. Photo: Courtesy of the Author

Why Do Salt Shippers Use End-Of-Life Cars?

They do for many reasons, but the primary one is the simplest: Salt is corrosive.

Here is where corrosive cargo meets economics. Rail cars are worth their cost if you can get them to last the 50 or so years they were built for. Salt is so corrosive, and the cost to repair serious corrosion damage so high, that it has never made financial sense to use newer cars in this service.

Conversely, if an old car’s next stop is the scrap yard, the condition of its lining or coating no longer concerns the shipper. They run the car in salt service for as long as it safely lasts without maintaining its corrosion protection, and then discard it. The cycle repeats as another aging car replaces the prior one.

But in the last few years, end-of-life replacement cars have proved harder to find and the cycle is interrupted. Another look at economics helps illustrate how that interruption can cause problems.

Rail cars are not the only way to move salt in bulk, but they are one of only two ways to do it cost effectively at scale. Like any shelf-stable cargo, shipping it by rail or boat simply cannot be beaten on a cost-per-mile basis.

Buyers are the beneficiaries. They have enjoyed a predictable, low-cost supply of salt partly because of how shippers have chosen to deliver it. But if the shortage of this sector’s rolling stock persists, that won’t be the case for much longer.

The impacts ripple outward:

- It could take longer for shippers to locate end-of-life cars for salt service;

- Salt shipment intervals would then lengthen, so distributors draw down reserve supplies faster;

- Meanwhile, salt storage sheds upstream fill up faster and stay full;

- The cost to ship salt begins to rise as shippers work harder to keep shipments on schedule; and

- The cost to buy salt also rises because the added cost of its movement is passed on to end users.

Something must give. Though shippers may not want to hear it, here’s a potential way out: Maybe it’s time to put younger rail cars in salt service.

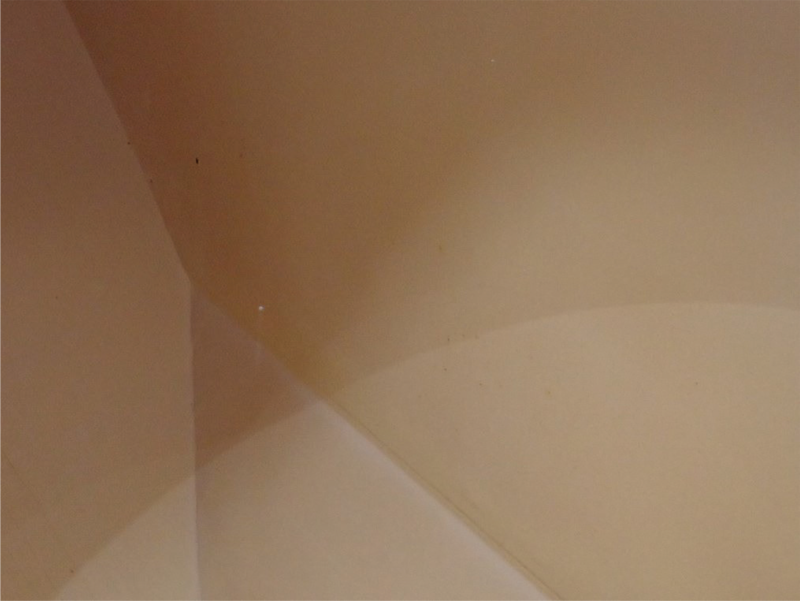

Fig. 2: The corrosion protection package for this hopper car in salt service consisted of a zinc-rich primer followed by an epoxy. The photograph was taken five years after system installation. Photo: Courtesy of the Author

Rethinking Corrosion Protection for Salt Service

This section is titled “Rethinking,” but maybe more appropriately, we should focus on simply thinking about it at all.

The experienced shipper knows that in today’s current way of operating, it is cost-prohibitive to apply and maintain even minimum corrosion protection for salt cars, which would consist of one or two coats of epoxy on the interior and a single coat of direct-to-metal (DTM) epoxy on the exterior. Salt would ruin that system in two or three years, the same duration the car would be in service if it hadn’t been lined or coated at all. But the math pencils out differently if shippers treat salt cars less like salt cars and more like other steel assets exposed to corrosive attack.

For salt car linings, consider a low- or no-VOC, thin-film, self-priming, hybrid elastomeric polyurethane. Thin-film versions of these advanced formulas offer exceptional barrier properties, strong abrasion resistance, great flexibility and elongation for impact and reverse impact damage resistance, and excellent protection against corrosion in aggressive environments. They’re safe, too: 100%-solids options make confined-space application better for rail car lining applicators.

Provided a hybrid elastomeric polyurethane rail car lining is properly maintained, it is plausible to expect twice the service life or longer with no total blast or reline.

For exterior corrosion protection, consider a conventional organic zinc-rich primer followed by an epoxy. Compared to the more rudimentary direct-to-metal epoxy coatings typical of most rail cars, the sacrificial zinc in a zinc primer provides galvanic protection against corrosion.

It’s true that a more comprehensive system consisting of zinc primers is ordinarily off the table for any rail shipper because the added cost and shop time is not worth what amounts to overkill corrosion protection. But for salt shippers, that overkill is compared against doing nothing, and today’s shortage of end-of-life salt cars means doing nothing is no longer feasible.

As with hybrid elastomeric polyurethanes, it is not outlandish to double the expected service life of a salt car when its zinc-epoxy exterior corrosion protection system is properly maintained.

Fig. 3: The interior lining of this salt car consists of a single coat of epoxy. Its poor condition is typical of a car in salt service. Photo: Courtesy of the Author

Is Today’s Shortage Just a Blip?

It is difficult to answer this question definitively, because rail car construction trends are hard to predict, and commodity shippers’ behavior under changing circumstances is even more so. But, in general, pessimism prevails owing to a few macroeconomic conditions.

First, hopper car construction dropped off in 2008 after a handful of years in which shops collectively turned out around 20,000 units a year. That drop coincided with market demand for hoppers at the time, which was weak. Shippers found enough existing rolling stock, so they didn’t need to order any new. With fewer cars built a generation ago, fewer will be available for salt service in their old age.

Second, hopper car construction took another hit during the COVID-19 pandemic. As whole sectors of the economy shut down, car shops scaled back operations, laid off staff, and some stopped work completely for weeks.

Third, and also related to the pandemic, is the persistent volatility across practically all sectors involved in rail car production that the industry still confronts today. That ranges from raw material shortages to soaring material costs to a more competitive labor environment. So even though the North American economy is strong, and even though demand for hopper car capacity is growing, shippers remain sensitive to high construction costs and more of them make do with existing cars than would be expected.

Salt shippers reliant on older cars have already noticed that these units are harder to find, and it’s going to get harder still. Broad trends suggest that it may stay that way for a long time.

Fig. 4: A hybrid elastomeric polyurethane lining as seen five years after installation in a hopper car in salt service. Photo: Courtesy of the Author

Conclusion

Salt shippers should put newer, or maybe even new-built, cars into service. That’s expensive, and so is applying a more robust corrosion protection package—at least in terms of dollars up front. But this paradigm shift will pay off later in the form of better-protected and better-maintained cars that stay on the rails longer.

No one in the supply chain has a better shot to change the game for the better than the shippers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Matthew McDonald, Director of Rail Sales

Carboline

Matthew McDonald is Director of Rail Sales for Carboline and is based in Philadelphia. He has 34 years of experience in high-performance industrial coatings and previously held positions with Sherwin-Williams, Jotun and PPG. He is an SSPC-certified Protective Coatings Specialist and a NACE-certified Coating Inspector.

Tagged categories: Features; Rail; Railcars; Salt exposure